In an opinion piece published by University Affairs last July, Julia Eastman offered some thoughtful reflections on university autonomy in Canada, noting in the first instance that the erosion of decision-making authority in our country’s universities appears to be “part of a global phenomenon.” She drew attention furthermore to that rather strange international dynamic presently prevailing in which governments hitherto inclined to control educational institutions seem to be “stepping back,” while those “historically less interventionist” are seeking to strengthen their influence over universities.

Whatever local circumstances are giving rise to these divergent trends, the lesson is obvious: now, as ever before, the autonomy and the defining values of universities are not guaranteed, either by governments or the societies over which they preside; and there is a need for institutions collectively to define as well as refine the way in which universities are conceived, to enunciate that conception, and to monitor the health of that understanding of the university mission in all corners of the globe.

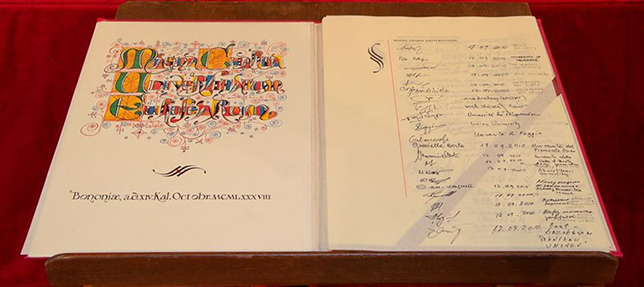

In 1988, on the occasion of the 900th anniversary of the University of Bologna, 388 rectors and heads of universities from across Europe and elsewhere signed the Magna Charta Universitatum (MCU), a declaration that enumerated the defining attributes of universities in the European tradition, and did so “as a guideline for good governance and self-understanding of universities in the future.” A precursor and a building block for the European Higher Education Area established 10 years later with the Bologna Declaration, the MCU was – and remains – critical to the enhancement of student and faculty mobility. It is, in short, a key element in the emergence of the global academy as a network of institutions collaborating for the education and elevation of peoples around the world. At the MCU anniversary conference in Salamanca, Spain, this past September, 70 new signatory institutions brought the total close to 900, drawn from almost 90 countries.

Those numbers speak to a remarkable global consensus on what might be desirable in a university – this is articulated in the “fundamental principles” section of the MCU – but they also surely raise the question of diversity. The first fundamental principle notes that the societies within which universities are situated are inevitably “differently organized because of geography and historical heritage.” So, despite certain shared generic characteristics, the MCU recognizes that universities across the world will differ widely under the influence of local circumstance.

After 30 years, the MCU is being revised in recognition of the changing landscape of global higher education, and of new dimensions that have opened up in the university mission. Despite the considerable value that non-European institutions have evidently found in the original declaration, its Eurocentrism is inescapable: “A university is a trustee of the European humanist tradition,” runs the fourth fundamental principle. In the preamble we are told that, “People and states should become more than ever aware of the part that universities will be called upon to play in a changing and increasingly international society” – a promising assertion, except that “international” in the MCU is actually synonymous with “far-reaching co-operation between all European nations.”

While the 1988 text of the MCU is limiting in this way, signatories have in practice behaved as if the language is not exclusive, and as if “society” has merely become “international” to an extent far beyond what was imagined by the original authors yet in a manner entirely compatible with their vision. Whether that last assumption is sound might be debated, but today the question is largely moot: the MCU is now “owned” by the broader international academy and is used across the world to shape, guide and defend university values. MCU 2.0 is expected to reflect that new reality.

The 31st anniversary conference of the MCU will be held this year on October 16-17 at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Currently nine Canadian institutions are signatories, but our hope is that many others will attend the conference and sign on. Universities Canada has convened several meetings and workshops to advance university autonomy and academic values within our country. The Magna Charta Observatory is pleased to be cooperating with Universities Canada to extend that project onto the world stage.

Patrick Deane is president and vice-chancellor of McMaster University, principal-designate of Queen’s University, and a member of the MCU 2.0 steering group.

Patrick, To my great surprise the MCU fails to state what the fundamental purpose of the university is, namely, in a word, INQUIRY – free, open, radical (going to the roots) inquiry in pursuit of self-knowledge (ie knowledge of ourselves and our relation to the world). Without this purpose that distinguishes the University from all other institutions, it is hard to see why governments would guarantee its autonomy or its freedom. I am here repeating the argument of Stefan Collini in What Are Universities For? Here’s a close paraphrase: the purpose of the University is to extend and deepen human understanding of ourselves and the world, through open-ended, disciplined and critical inquiry.

Peter