This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

My sister and I are both professors. A few years ago, in the wake of the global financial crisis, she faced the possibility of a six percent pay cut. She joked to me over the phone one night, “What am I going to do — have six percent fewer thoughts?”

So naturally, when I learned that the University of Toronto pays female professors 14 percent less than male professors, I wondered whether my employer thinks I have 14 percent fewer thoughts.

I was researching the gender pay gap in order to lead an informal discussion in my department. We have a group that meets to crunch numbers on why there are so few female science professors. I ended up doing a deep dive into the publicly available data on professor salaries.

Statistics Canada figures show that the University of Toronto paid male and female professors median salaries of $168,425 and $145,150, respectively, in 2016-2017. This is a difference of $23,275 a year, or 14 percent. Over a 30-year career, this could add up to nearly $700,000 in lost income, a number that keeps me up at night.

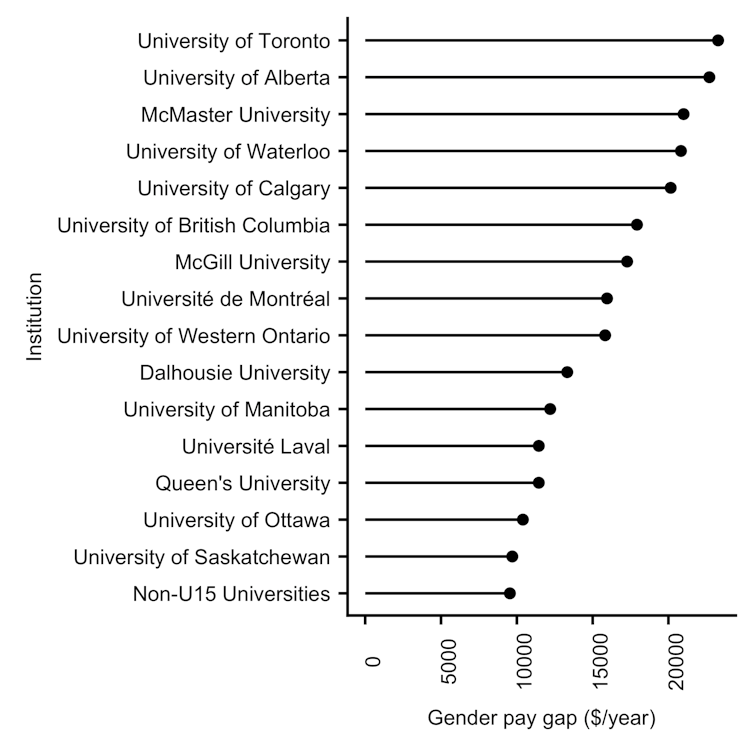

The University of Toronto is not alone in paying female professors less. There is still a gender pay gap at nearly all Canadian universities, with especially big gaps at Canada’s 15 research-intensive universities, known as the U15.

Nationally, male professors were paid a median of $136,844 while female professors were paid $121,872 in 2016, a difference of $14,972, or 11 percent.

Ever curious, I wanted to know why.

It’s not because men are better researchers

“Why?” is a data-hungry question.

Luckily, since 1996, Ontario’s “sunshine list” has published the salary of every professor in the province who earns more than $100,000 a year. This data set tends to underestimate the gender pay gap because it includes only professors making six-figure salaries, but it is rich in other ways. Salary data are available for more than 16,000 individual professors, in some cases going back 20 years.

Salary should reflect merit, but a professor’s merit is not easy to measure.

I know this first-hand from spending countless hours poring over professors’ CVs and research proposals for the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). I am on a committee tasked with boiling down a professor’s accomplishments to a single number: The dollar amount they will receive as a Discovery Grant.

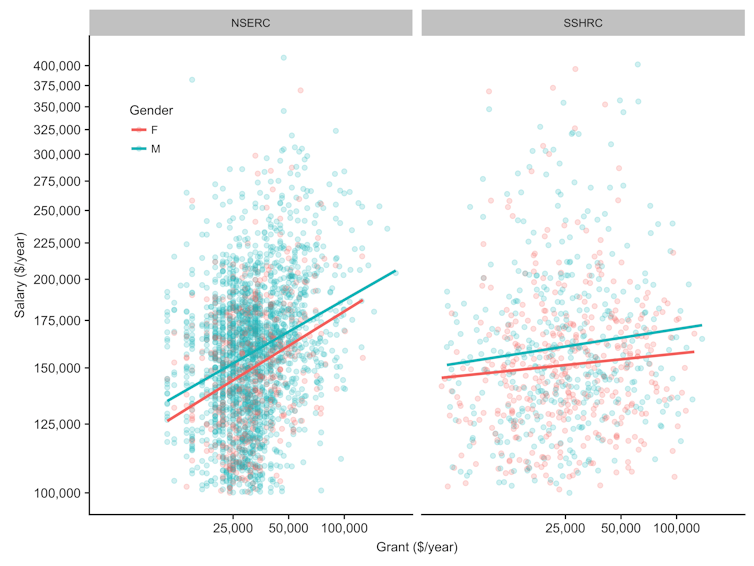

The results are publicly available from NSERC, as are Insight Grant awards from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), making it possible to combine grant and salary data for thousands of Ontario professors. These data sets do not include gender, but computer programs can infer gender from first names with high accuracy. (I used gender in the programming language R.)

Among all professors on the sunshine list, women were paid $9,921 less than men in 2016. Accounting for grant size hardly moves the needle, as women are paid close to this much less than men even when they get the exact same funding.

In other words, the gender pay gap is not because men bring in larger operating grants and therefore merit larger salaries. Also, the gender pay gap is slightly larger among professors getting grants from SSHRC than from NSERC, suggesting it is not driven by the scarcity of women in highly paid natural science or engineering fields.

The ghost of sexism past?

Some professors, mostly men, still working today were hired in the 1980s or even earlier. The gender pay gap at universities may be partly the legacy of gender bias in hiring that dates back several decades.

The highest paid professors are generally those who have worked at a university longest, so there may be few highly paid women now because universities hired very few women 30 years ago. However, the median male professor has been on Ontario’s sunshine list for only one year longer than the median female professor (seven versus six years, respectively).

Of course, I don’t know how long they were employed by a university before earning six figures. Still, the gender pay gap of today does not appear to be simply a holdover from discrimination of long ago.

My discussion group wanted to know more. What about race? The mommy penalty? Gender bias in tenure and promotion? Salary negotiation?

These are hard questions to answer with publicly available data, but universities can and should (and indeed sometimes do) study these factors with data collected by their human resources departments.

The gender pay gap is not a new problem. Ontario has legislated equal pay for equal work for over 30 years. It’s high time universities valued male and female professors equally.

Megan Frederickson is an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto.

As Megan Frederickson points out at the end of her article- equal pay for equal work needs no further evidence or “admiring” as a problem. We even have the solutions worked out but universities, including my own, claim to not have the money to solve the problem. Every budget season is about tough decisions in the face of true financial hardship in higher education. I was also struck by the reference to “six per cent fewer thoughts” as my own pay gap began when I was not placed on the Assistant Professor grid until the “terminal degree” was awarded by my university. Did I hold back on my doctoral thoughts? On the face of it, my pay-wait seemed only right and certainly accounted for in collective agreements- until one examines the variation in “terminal degree” decisions taken across academic fields as well as the historical inequitable implementation of this practice.

As all women know, there is no “catching up”. As the 3rd woman promoted to full professor (ever) in the my department ,in the history of the entire university, I also know that hard work and achievement will not have enough time to pay off.

Just curious – are starting salaries for men and women the same at these universities? If so, is there any longitudinal study tracking the salaries of male and female who start off earning the same salary? Could it be that in some cases, male & female professors start off with the same salary, but then some male professor’s salaries increase at a higher rate? And if so, why? At our university there is a pretty rigorous faculty evaluation process, in which many female professors participate. It is hard to believe that the evaluation committee operates on a gender bias, deciding collectively to grant more merit points to men. Is it that men publish more and thus get rewarded more, and if so, why is that the case? The numbers provided in the article, alone, do not tell us all we need to know.

Unless I have overlooked some way to manipulate the data, the Statistics Canada data I have seen are worthless for deciding whether university salaries differ for men and women because of gender bias. Stats Canada lumps all ranks together (including Deans) in producing the gender statistics despite the fact that the percentage of women decreases from Full (28%) to Associate (43%) to Assistant (49%). Controlling for rank would eliminate much of the difference shown in the first graph. It would also be necessary to examine years at rank, especially for Full professors and perhaps also for Associates given that is the terminal rank for some professors. The article wants to blame gender bias in past hiring, but the reality is that the proportion of women with requisite PhDs was much lower in the past than today.