In a bid to understand where PhD graduates end up after they finish their doctorates, the school of graduate studies at the University of Toronto launched a project to collect publicly available data on the roughly 10,000 U of T students who received their PhDs between 2000 and 2015. Called the 10,000 PhDs Project, it provides a snapshot of where these former students are currently in their careers.

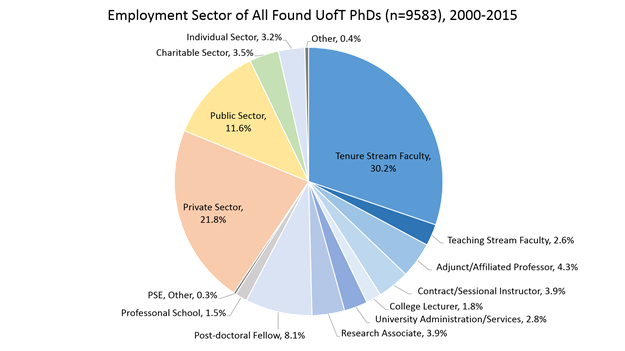

Just under 60 percent of the PhD graduates from U of T are working in higher education, the project found. This includes teaching-stream faculty, full-time and part-time lecturers, adjunct professors, research associates, postdoctoral fellows and university administrators. Less than one-third have tenure-track positions.

Humanities and social sciences have the largest share of PhD graduates in the tenure stream, with roughly 40 percent each, while physical and life science PhDs are more likely than their peers to be employed in the private sector. Hospitals and governments are the two major employers in the public sector, where 12 percent of PhDs in the study are currently working. The complete findings have been released to the public through an interactive online tool, and a series of mini-reports were created for different audiences, including students, government officials and employers. Data were also collected on graduates’ nationalities and where they went – geographically and by employment sector – after earning their PhD.

The 10,000 PhDs project was spearheaded by U of T biochemistry professor Reinhart Reithmeier. In 2012, he gathered a decade’s worth of data on his own department, which indicated that just 15 percent of former grads were working as professors. He recalled thinking to himself, after receiving the data, “that can’t be right.” Nevertheless, he said he was impressed with the outcomes, which spurred him to create professional development opportunities in his department.

“It blew me away. They are doing amazing things [with their PhDs],” said Dr. Reithmeier. “The issue was that I, as chair, didn’t know about that and most faculty members, except anecdotally, didn’t know. Most importantly, our students didn’t know about it.”

In January 2016, he pitched the idea of the 10,000 PhDs Project to the school of graduate studies as a way to be transparent about PhD outcomes. He hired a team of undergraduate researchers to compile data from public sources on the internet, such as convocation lists and social media. The group managed to collect data on 85 percent of past graduates, and by crosschecking their data with departmental alumni records, were able to bring the total to 88 percent. “We hope that our study will motivate other universities to accumulate employment outcome data for their graduate students, so they can make more informed choices as to their career paths,” said Dr. Reithmeier.

Increased graduate enrolment

In 2005 and 2011, the Ontario government gave extra funding to universities to increase graduate enrolment by 14,000 and 6,000 additional spaces, respectively. As a result, at U of T, the number of PhD graduates nearly doubled over a 15-year period. The largest increase was in physical sciences, followed by life sciences and then social sciences, while the number of humanities graduates remained constant.

“I think it’s important for government and business to better understand the role of graduate education,” said Joshua Barker, dean of graduate studies and a professor of anthropology at U of T. “Our best ambassadors are our PhDs and individually they’re making a tremendous impact, but there is something about seeing the whole and how this fits into the larger economy.”

Other Canadian projects have gathered and publicized PhD career outcomes: institutionally, at the University of British Columbia, for example; by discipline, such as the TRaCE project tracking humanities outcomes; and province-wide through the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario, or HEQCO. It was the HEQCO report (PDF), published in 2016, that provided the methodology for the 10,000 PhDs project, Dr. Reithmeier said.

The HEQCO study looked at the career outcomes of 2,310 doctoral students who graduated from Ontario universities in 2009. It found that just under 30 percent were full-time or tenure-track professors at a university, while another 21 percent had other jobs within academia. Over a third were employed outside academia in a variety of sectors; no employment data were available for the remaining 15 percent.

A Conference Board of Canada report, released in 2015, had slightly different numbers. It found that 40 percent of PhD holders work in the postsecondary education sector, but fewer than one in five – 18.6 percent – are employed as full-time university professors, including both tenure and non-tenure-track positions. The remaining 60 percent of PhDs went on to work in other sectors such as industry, government and non-governmental organizations.

Sally Rutherford, executive director of the Canadian Association for Graduate Studies, said data collection is top of mind for many university administrators, but gathering it in compliance with privacy legislation is not easy. “Everyone has anecdotes, but actually having real numbers is a challenge,” she said. Yet, “more and more institutions are engaging in some sort of tracking, for their own purposes. People can see a value in it, because there is a need to report more and more on how public money is being spent.”

Despite discussions about graduate reform over the past decade across institutions, cultural change has been slow to take shape, Ms. Rutherford said. “There are projects in different universities that have embraced new approaches, but overall I don’t think we’re there yet.”

At U of T, Dr. Barker said, “there’s always going to be a strong emphasis on training people for those top-flight tenure-stream jobs.” Nevertheless, the 10,000 PhDs Project may help facilitate institutional change, he said. “Once you have a better understanding of where your grads end up, you start rethinking what your program is and what the requirements are. … I would like to get to a point where students arrive at the university and, in the course of their program, what they see is different doors opening to what their future might be.”

Read Dr. Reinhart Reithmeier’s closer look at the numbers of the 10,000 PhDs Project.

This is a fascinating and critically important study that provides much-needed data and insight regarding the career paths of PhD graduates. Congratulations. It would be valuable to replicate at the national level, using this work as a starting common template. At the CIHR Institute of Health Services and Policy Research, we have been engaged in a PhD training modernization initiative focused on health services research (HSR) and, inspired by the 10,000 PhDs project, plan to track the careers trajectories of HSR PhD graduates across Canada.

I’ll bet that this study left out all kinds of folks about whom they could not find “publicly available data” – the ones who just gave up and aren’t working at all. I know several U of T PhDs who are in that situation.

Indeed, there is a correlation between graduate students who develop a robust professional network beyond academia along with a strong public profile (e.g., personal web-site, Linkedin profile, résumé, etc. ) and their future employability.