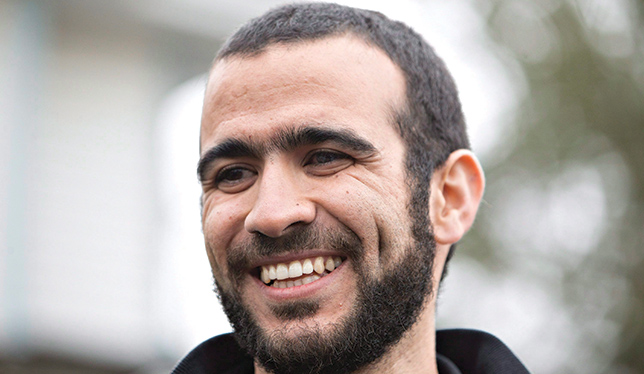

The King’s University is small, even by the standards of small, Christian liberal arts schools. Lodged between a plastics manufacturer and a suburb of mid-century bungalows in southeast Edmonton, the university features a concrete arch at the entrance that gives it the look of a neighbourhood mall, while a tower behind it makes it look more like a factory. Eight hundred students flow through its baby-blue-tinged halls, majoring in arts, humanities, music, science, commerce and education, all of it imbued by a Christian perspective “as followers of Jesus Christ, the Servant-King,” according to its mission. But there is a handful of students from other faiths and, last fall, one in particular stood out: a 29-year-old Muslim man with a trim beard.

Omar Khadr arrived wearing a bucket hat and a big grin. His blue backpack was a gift from the mother of King’s professor Arlette Zinck, his long-time tutor. He and Dr. Zinck met six years ago at Guantanamo Bay Detention Centre in Cuba, where Mr. Khadr, its youngest inmate, had languished since 2003 on charges of war crimes following a firefight between the Taliban and American soldiers in Afghanistan. A U.S. sergeant was killed and, though evidence is scant, U.S. forces contend that Mr. Khadr – who was blinded by shrapnel in one eye during the battle and had fist-sized exit wounds in his shoulder and chest – threw the grenade. He was 15.

Repatriate and educate him

That he is now free, well before the end of his sentence in 2018, may not have been possible without King’s advocacy. For years, the largely evangelical student body staged protests and symposiums arguing for his release, and urged faculty to help repatriate and educate him. Not everyone is happy with King’s position, and when Mr. Khadr stepped on to campus that September day last year, safety was uppermost on the minds of university officials. “Would our students and Omar himself be safe from someone who might want to hurt him?” wondered university president Melanie J. Humphreys.

The university stopped short of hiring security but encouraged people to give him space. Mr. Khadr is deeply private and, after 14 years as the subject of often vitriolic headlines, understandably avoids attention. (He declined to be interviewed for this article.) Nevertheless, much to his chagrin, Mr. Khadr has become a minor celebrity in Edmonton and on occasion must politely decline a well-wisher’s request for a picture. The situation at King’s was no different, especially amongst the senior students who took part in the activism that helped lead to his release.

“They were very excited,” recalls Britta deGroot, a recent graduate who was involved in the early advocacy efforts and is now the school’s inclusive postsecondary education coordinator. “Omar handled it well. He’s just a really welcoming guy and he’s always got this smile on his face that draws people in.” His presence was never disruptive to classes, she says, and with time the attention waned and Mr. Khadr was treated like any regular student. Ms. deGroot and he are now friends. Something that continues to amaze her, she says, is that he appears to hold no grudges. “He could easily be a jaded, angry person, but he’s not. It makes you wonder, where does that come from? How can I get that?”

The image of a smiling Omar Khadr was not the one first projected on the screen at a morning talk held at King’s in September 2008. The speaker, Dennis Edney, a dour Scot and human rights lawyer living in Edmonton, was invited to speak about Mr. Khadr, his client, during an event organized by the university’s initiative for global justice called the Micah Centre. Since he’d begun representing Mr. Khadr pro bono in 2005, Mr. Edney had struggled to find a receptive audience. He deliberately reached out to places of worship, assuming pious people would find the humanity in this young man that others had failed to see. He says he was met with “overwhelming silence, save for a few mosques.”

The theme of King’s biannual symposium was “invisible dignity.” Until then, the face of Mr. Khadr – other than a solemn passport photo of a pubescent boy – had been invisible to most attendees in the school gymnasium. Many were learning of the Toronto-born child soldier, who was thrust into explosives training by his radicalized father, for the first time. Those who were acquainted with the story had likely known him as the son of “Canada’s First Family of Terrorism,” as the Khadrs were dubbed by some in the media. It was standing room only.

“It’s hopeless”

After Mr. Edney’s speech the room was silent. Finally, a young woman in a hijab asked how she could help. Mr. Edney retorted with his usual spiel – write your Member of Parliament, tell your friends – but, he said, “it’s hopeless.” The kid was going down.

Then Mr. Edney exited the gymnasium and left campus.

“Looking across the room, watching the faces of these students,” recalls Dr. Zinck, “there was a sense of great discomfort.” She was disturbed by the story and, even more, by the message of hopelessness. Powered by tenets of reconciliation and renewal, King’s mission encourages action. Throughout that day, students’ silence turned to outrage and they began pressing faculty for answers. Dr. Zinck returned to the room before day’s end to speak. “You’ve heard an impassioned advocate, [but] you’ve heard one story. There’s always more than one story. As university students, as people of faith, your duty and obligation is to do your intellectual work. Get out there. If you’ve been moved by what you’ve heard, and if you still feel motivated to do something, then do it. Because we don’t do ‘hopeless.’”

A month later, during an all-candidates debate hosted at King’s for the 2008 federal election, a student asked what the candidates planned to do for the young Canadian detainee, who had been tortured and detained at Guantanamo without trial for five years and counting. “There’s no doubt about it, it is an injustice,” said the riding’s Conservative Party incumbent Rahim Jaffer. But in the days that followed, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper took a much more hardline stance, refusing categorically to extradite Mr. Khadr from Gitmo.

The federal government wasn’t just complicit in a national disgrace, but was an active partner

To student Geoff Brouwer, who had asked the question at the debate, this proved that the federal government wasn’t just complicit in what he termed a national disgrace, but was an active partner. “We spend a lot of money on democratic reform in fragile states and ensuring there is rule of law. What’s the point of preaching the gospel of democracy if we don’t honour it at home?” he asks. Against the backdrop of the federal election, the Afghan War and presidential front-runner Barack Obama’s calls to close Gitmo, Mr. Brouwer, who is now 27 and works in Ottawa as an economist, says he felt like a participant in a larger movement.

“Having Dennis stand there, the degree of separation became one,” recalls English student Sharon Alles. Soon, she, Mr. Brouwer and others were ironing Mr. Khadr’s portrait to T-shirts with an X over his mouth to represent Canada’s collective silence. Some 40 students wore them on campus and refused to speak for an entire day, upsetting some professors. One group, Micah Action and Awareness Student Society, organized a protest in downtown Edmonton with members of the city’s largest mosque, Amnesty International and the University of Alberta.

This culminated in a panel discussion at Edmonton’s Winspear Centre for the performing arts downtown. The guests were Mr. Edney and journalist Michelle Shephard of the Toronto Star, who’d reported extensively on Mr. Khadr. More than a thousand people attended. “King’s is very small,” says Ms. Alles. “It’s the kind of place where things just sort of happen and everyone gets swept up in it. Then you look around and you don’t know how it got started. It’s this beautiful microcosm of self-organization.”

One can’t simply write to a Gitmo prisoner

Another branch of students, somewhat naively, organized a letterwriting campaign to Mr. Khadr in Cuba to express their sympathy and support. After several months, they realized one can’t simply write to a Gitmo prisoner and asked Mr. Edney to be their postman. Mr. Khadr received so many missives that he mixed up people’s names on his return letters and students would have to exchange them until they found one that sounded like it was addressed to them. Mr. Khadr did not, however, misaddress his letter to Dr. Zinck, who encouraged the inmate to find peace in books. Soon after, Mr. Edney asked the English professor to educate Mr. Khadr through ad hoc correspondence, violating strict Pentagon rules. Until the lessons were officially sanctioned, Mr. Edney went to great lengths to deliver Dr. Zinck’s lesson plans – usually book analyses based on what was in stock at Gitmo’s small library – by smuggling them under the insoles of his shoes or hiding them within his client’s 1,500 pages of legal briefs. Mr. Khadr’s assignments were returned in numbered and bulletpointed order, like legal briefs themselves.

“King’s stands above every other organization [in its support],” says Mr. Edney. “Formerly, people would give me a clap, and I’d leave and never hear from them again. But they embraced Omar’s story in a manner that I hadn’t seen in my travels on his behalf. That was an amazing transition in my journey. It gave me some hope.”

Dennis Edney is not a man of organized faith and his knowledge of King’s was initially very limited. His eldest son was a student there, but Mr. Edney knew the university better for a civil rights case that put it on the wrong side of history.

In 1991, Delwin Vriend, a chemistry instructor and alumnus, was fired by the school after he came out as gay. Mr. Vriend appealed to the Alberta Human Rights Commission but his appeal was rejected because the provincial law did not include sexual orientation as a prohibited ground of discrimination. The landmark suit eventually made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada and forced a rewrite of the human rights code, leaving a stain on King’s reputation. “The situation with Delwin Vriend really broke our community,” says Dr. Humphreys. “Maybe you can’t draw straight lines to Omar Khadr, but it gave us an openness, awareness and sensitivity to ways people aren’t receiving full justice. We learned some important things as a community about how to embrace differences.”

“You’re Christian, he’s Muslim. So why do you care so much?”

Despite that, there was some opposition to the students and faculty members defending Mr. Khadr. Many within the institution’s conservative Christian community had military ties and were disgusted by Mr. Khadr’s alleged crimes. “There were friends of mine who thought he should rot in prison,” recalls Mr. Brouwer. Ms. Alles recalls an argument with her father: “He said, ‘You’re Christian, he’s Muslim. So why do you care so much?’”

Several donors withdrew their funding (though Dr. Humphreys says the impact was negligible) and Dr. Zinck personally received threatening letters that were scary enough to involve police. Conservative media personality Ezra Levant accused her of turning King’s into “a factory for Khadr groupies.”

The controversy peaked in August 2010 with Mr. Khadr’s long-awaited military trial at Guantanamo. Mr. Edney asked Dr. Zinck, herself the child of a parent in the military, to testify as to her student’s good character. By all standards, the trial was a farce, says Dr. Zinck (though she has kept a memento from that time: hanging in her office at King’s is a framed, original drawing from Mr. Khadr’s trial signed by Janet Hamlin, Gitmo’s official court artist). Mr. Khadr pled guilty on all counts in exchange for a reduced sentence from 40 to eight years and the possibility of an eventual transfer to Canada. Also as part of his agreement, Mr. Khadr was allowed an in-person education taught by Dr. Zinck. “That’s the moment things changed,” she recalls. “Because it was the moment that Omar Khadr ceases to be the object of my students’ care and concern and becomes my student. Our student.”

After the 2010 trial, Dr. Zinck recruited professors from across Edmonton’s three universities to design and implement an interdisciplinary curriculum for Mr. Khadr built around Canadian literature. For example, Mr. Khadr read Thomas Wharton’s Icefields then undertook a physics lesson on calculating height from a mountainside. The lessons went on for four years – through the duration of Mr. Khadr’s time at Gitmo, where Dr. Zinck saw him twice more, and after his 2012 repatriation and transfer to Canadian custody.

But Dr. Zinck was more than an educator and confidante. Like Mr. Edney, she became an advocate, speaking of Mr. Khadr’s appetite for learning, his humbleness, his peacefulness and warmth. More contentiously, she began to speak of his innocence once he retracted his guilty plea following extradition.

Reigniting Mr. Khadr’s cause

In 2011, Dr. Zinck’s lecture to a University of Alberta Islamic studies class would reignite Mr. Khadr’s cause, which had lost much of its energy after the original cohort of King’s student-activists graduated and moved on. It was there that Dr. Zinck met Muna Abougoush, a 21-year-old philosophy student who admitted to being somewhat embarrassed that she hadn’t heard of Omar Khadr before.

Ms. Abougoush was active in student groups, raising awareness of the humanitarian crisis in Darfur, but the magnitude of that crisis left her feeling that her efforts were futile. Mr. Khadr’s case was different and felt more personal. He was just one human being, close in age and, like her, from an Arab-Canadian and Islamic household. The parallels disturbed her. “The way [Dr. Zinck] was involving her community, I wanted to involve mine,” says Ms. Abougoush. While forging relationships with the Islamic community and fellow U of A students, she co-founded the group Free Omar Khadr Now with the help of Dr. Zinck’s husband Rob Betty and Aaf Post, a Netherlands designer who spearheaded a robust social media campaign.

It was the first formal group advocating for Mr. Khadr’s release and raising funds for Mr. Edney, who was becoming financially drained by the case. The group formalized Mr. Khadr’s advocacy in a way that King’s couldn’t, at least officially. Still, Ms. Abougoush credits the Christian university for legitimizing Mr. Khadr’s cause. “That they were advocating for him had a major influence on public opinion because people valued their opinion. And they’re people with a lot at stake. They had a lot to lose.”

“I told him he would be welcomed at King’s”

King’s didn’t take an official position on Mr. Khadr until January 2015. Until then, any student and faculty supporters were acting on their own behalf. But, as his bail hearing neared in May of that year, Mr. Edney asked King’s president Dr. Humphreys – who had only just started at King’s in June 2013 – to write a letter stating the university’s intent to accept him as a student if he were free. This, they hoped, would help his case by proving that a reputable institution would embrace him on the other side. But first, she had to meet the prisoner.

Along with Dr. Zinck, Dr. Humphreys drove the two hours to a medium security prison in Bowden, Alberta and “everything that I’d heard about him was confirmed,” she says. “He was thoughtful and engaged. We talked about his day-to-day routine, the culture of incarceration and some of his schoolwork. And then, the future: I told him he would be welcomed at King’s.”

On May 7, 2015, Mr. Khadr was freed on bail by the Alberta Court of Appeal and released under the supervision of his lawyer Mr. Edney. Mr. Khadr asked Canadians at the time to give him a chance to show he was worthy of their trust. “I will prove to them that I’m more than what they thought of me. I’ll prove to them that I’m a good person,” he told reporters.

At King’s, students are assigned a personal advisor and that fall Mr. Khadr was paired with Dr. Zinck. Every day she would drive to the opposite side of the city to pick up Mr. Khadr from Mr. Edney’s home, where he is treated like a third son, drive him to King’s and drop him back off after school. They have become close friends.

The biggest challenge of being free was learning to show vulnerability again

The sabbath year, or shmita in Hebrew, is the final year of the seven-year agricultural cycle mandated by the Torah and mentioned in the Bible. It was a Sabbath year in 2008 when Dennis Edney gave his Micah Centre talk at King’s. And it was a Sabbath year again, in September 2015 – exactly seven years later – when Omar Khadr gave his talk at the same podium. Wearing a black suit and black shoes, he was joined on stage by one of his former correspondence instructors, Micah Centre director Roy Berkenbosch, for a discussion on the theme of “playing God.” Mr. Khadr was visibly nervous. There were 600 people in attendance and he wrestled for weeks about whether to take the invitation. “I’m just freaking out right now,” he admitted to Mr. Berkenbosch in between laughs.

After gaining his composure, Mr. Khadr told the audience that the biggest challenge of being free was learning to show vulnerability again, to express his emotions, after 12 years in prison. The best part, he said, was interacting with people who had no ulterior motives.

“How’ve you maintained hope for the future?” asked Mr. Berkenbosch. Mr. Khadr took a deep breath. “A few years ago, I realized that if you want something so pure, you have to get it from its original source. And the most pure hope is from God. Once I realized that and embraced it … hope opened a lot of doors for me, to bypass the anger that might restrict me.”

In the 16 months since his release, Mr. Khadr indeed seems to have bypassed any anger and by all accounts is thriving in Edmonton. He finds peace and anonymity in outings to West Edmonton Mall, where he blends in with the crowds, and by tearing along the city’s tranquil, forested river valley on his bike for kilometres on end. This spring, he completed a high school diploma while earning postsecondary credits from King’s as a student of Western civil history and physical education. He is attending King’s again this fall to upgrade a number of science courses in preparation for applying to nursing school.

Omar Mouallem is a National Magazine Award-winning freelance writer based in Edmonton.

I was part of the Free Omar Khadr group from the very beginning and heard his lawyer talk. I am delighted that he is doing well. The chances that he threw the grenade that killed an American are very slim indeed; he was found clinging to a wall and screaming to be shot he was in such pain. What the American military did not want us to know was leaked: that is, another man there almost certainly threw the grenade and he was shot when more Americans came in.

God Blessings on each and every one of you good people who see past what the media wants us to believe.

Does my heart good to know more good people exist over bad ones.

Please correct the spelling of two names: Geoff Brouwer and Sharon Alles.

The names have been corrected, thank you. We apologize for the errors. To see a photo of Ms. Alles, Mr Brouwer and others advocating for Mr. Khadr’s release back in 2010, see here (PDF):

http://www.calvin.edu/library/database/crcpi/fulltext/banner/2010-1000-0013.pdf

Bravo people of King’s University who cared enough to do so much for one man whose situation seemed hopeless. The story of this man’s grace and resilience and your compassion and dedication to his cause, renews my faith in humanity. I would like to thank the woman who asked Omar’s lawyer what she could do to help. Had she not done that, perhaps none of the rest would have happened. One voice.

What a story of Micah 6:6-8, in action, (especially vs 8).

I’m a middle-aged proud and out gay man, a former student of The King’s University in its infancy (I studied at the then “The King’s College” from 1980-1982) and a former staff member (I worked there as a student recruiter from 1986-1987). Delwin Vriend was a friend of mine, and while I didn’t have the courage to do what he did when I was employed at King’s and come out publicly as a gay man (I didn’t come out until 1989), I can certainly attest to the accuracy of Dr. Humphrey’s statement that the Vriend case broke the King’s community. It also shattered forever my trust and faith in the “faith” community from which King’s originated. To read this story, and to read Humphreys’ comments that the Vriend case “gave us an openness, awareness and sensitivity to ways people aren’t receiving full justice. We learned some important things as a community about how to embrace differences”, leaves me hopeful that even the hardest of opinions can indeed be changed, the most dogmatic of beliefs can evolve, and communities can indeed learn to embrace difference. Kudos to the King’s University (and Dr. Humphreys) for having the courage to live its faith.